Futurism Restated #89: Maybe We Should All Just Stay Home (Not Really)

Notes on Lisbon: the scourge of tourism and the resilience of culture

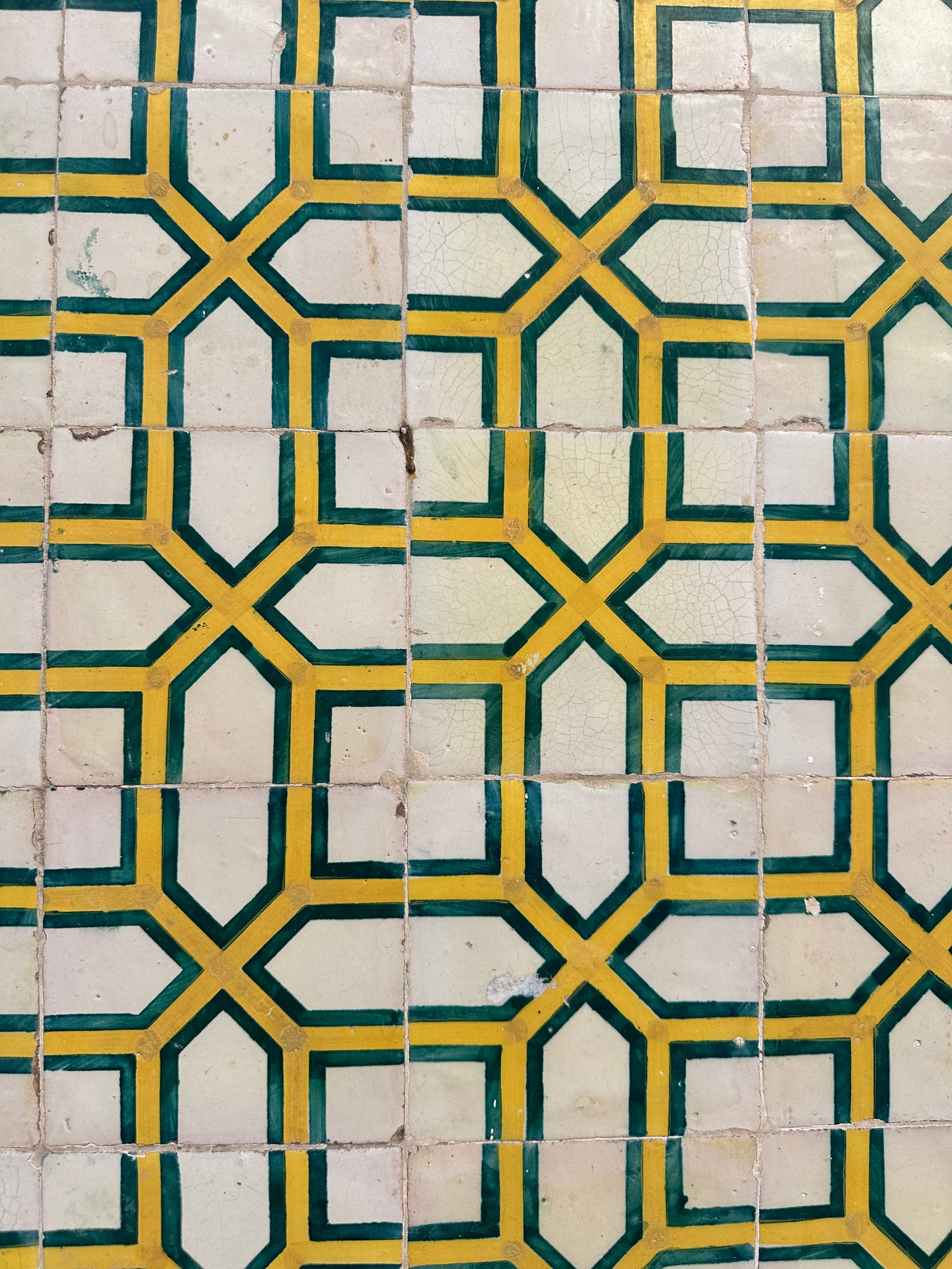

I was in Lisbon over the weekend with my wife and daughter, for four days of badly needed vacation—extended by two more days once storms in Barcelona forced the cancellation of our flights home, stranding us in Portugal for 48 hours. (No complaints! I’m writing this from our friend’s very cozy flat in Chiado, with the cathedral visible from where I sit on the sofa.) It’s the first time I’ve been back to Lisbon since I was here 10 years ago to profile Panda Bear for Pitchfork. I loved it then and I loved it even more now. Lisbon is a beautiful, vibrant city, the kind that requires no particular plan—just use your feet, and you’ll be rewarded. We particularly enjoyed the Sunday ferry trip to Almada, across the river, where we spent the day roaming the hills, taking in the mixture of faded architectural grandeur, run-down ’60s buildings, community gardens, stray cats, and the crumbling docks of the Rua do Ginjal.

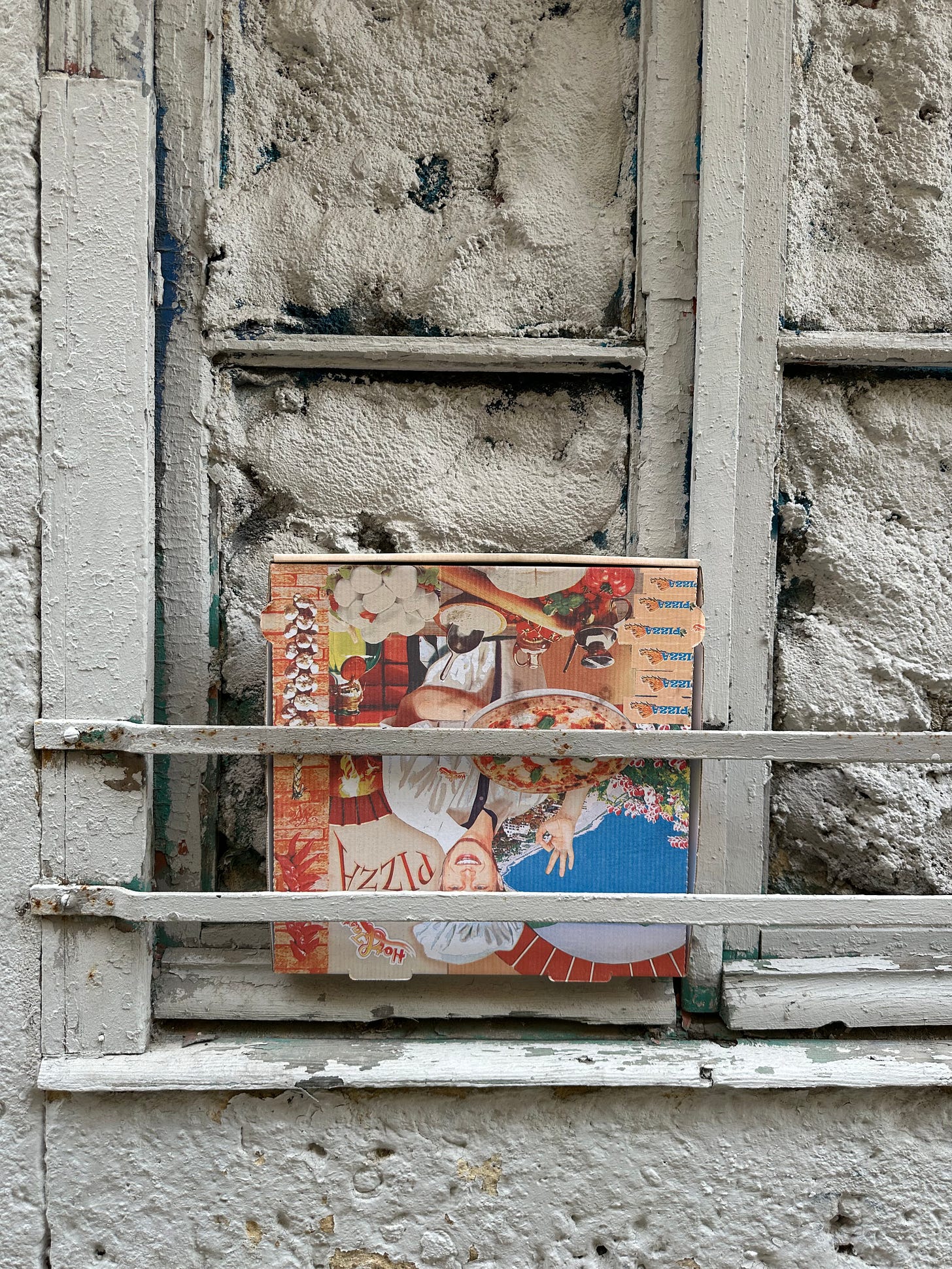

However: I don’t think I’ve ever been to a place where overtourism appears so catastrophic. We stayed in a friend’s apartment in the gridded downtown area. His flat, which he’s had for 10 years, is homey and charming, but everything around it is an inferno of tourist traps and tuk-tuks, a Disneylandish hellscape that makes Barcelona’s Ramblas look low key. In the window of the cutesy bakery next to my friend’s street sit translucent ziploc bags with a blush-colored liquid inside. Confused, I peered closer to decipher the label: “THE BAG I Deserve,” read the text beneath the illustration of a hand swinging the ziploc, as though it were a purse. “Aperol Spritz made by Benedita.” I feel like pre-mixed, pre-sealed to-go baggies of Aperol Spritz tell you everything you need to know about the way the local economy is trending.

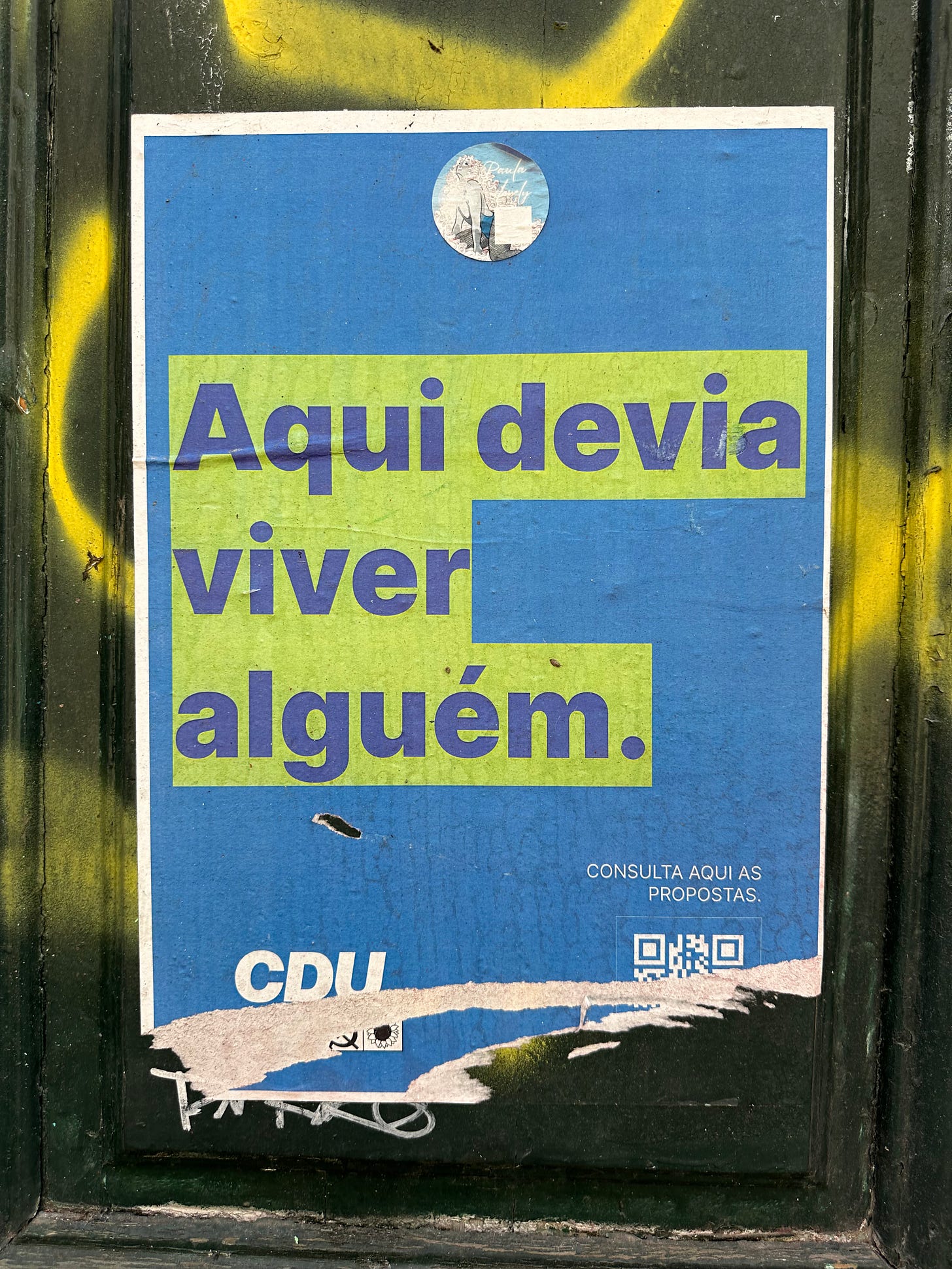

I don’t know how long the center has been like that; I don’t recall it looking so bad a decade ago, but I didn’t spend much time there, either. But it’s clear that all the life has long since been squeezed out of the place. There’s not a single grocery store or fruitseller, not a single shop to cater to residents, aside from a handful of haberdasheries that I can only assume won’t be long for this world. It’s a dead zone. Worse: It’s a zombie playground. Things got even worse on Saturday, when we hit the Feira da Ladra, the flea market. A fine little market, and the quiosco in Parque de Cães was a treat: excellent pastries, a multicultural mix of locals and tourists, a street musician busting out dubby live jams on synth and drum machine. Vibes. But walking back down through Alfama we were horrified by the sheer numbers of tourists, a veritable flood of phone-toting invaders, along with a nonstop juggernaut of tuk-tuks. It made Barcelona’s Ramblas look like a small-town residential neighborhood, by contrast. I felt bad for having come to the city; I felt like part of the problem.

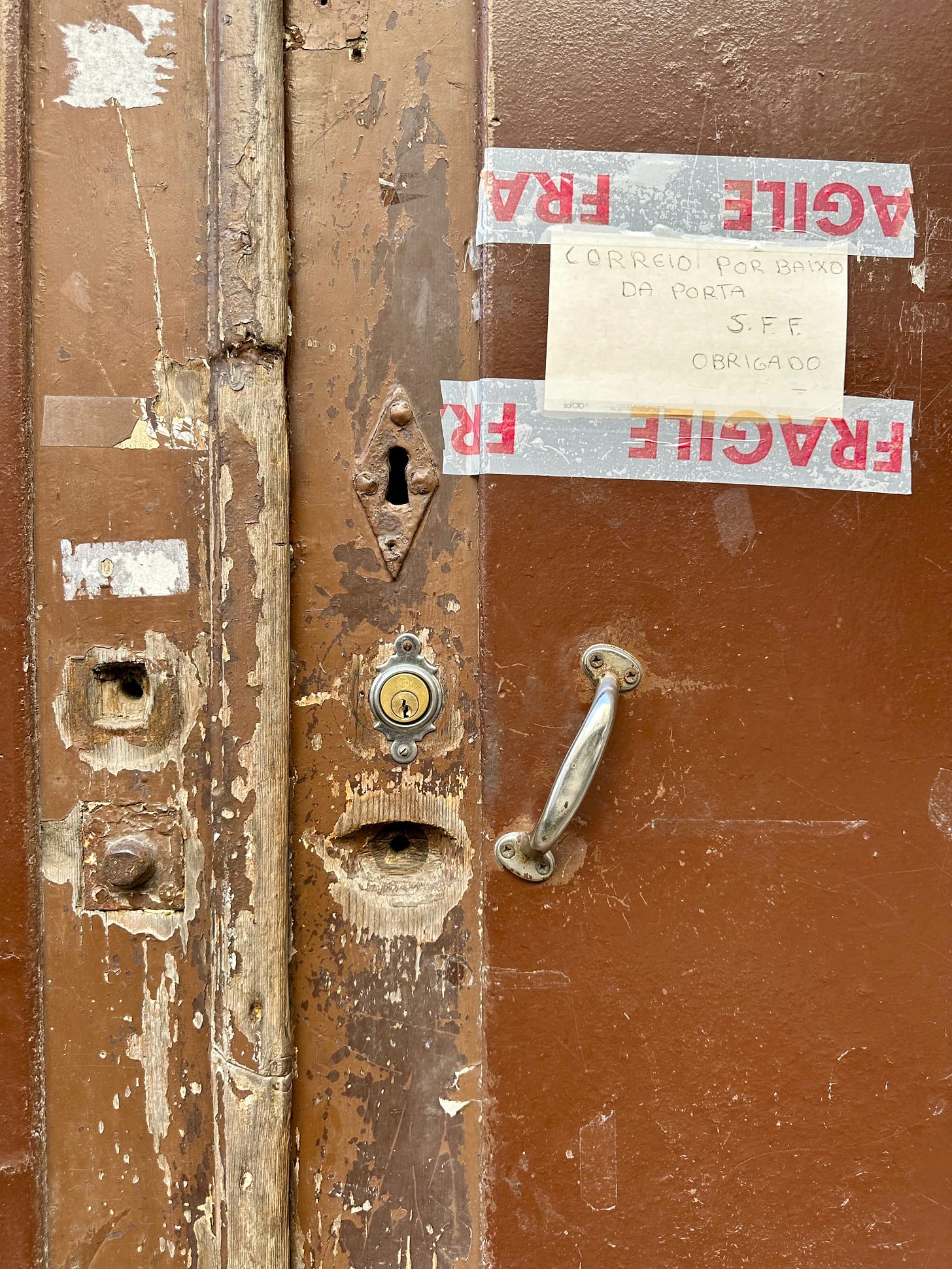

In other parts of the city, my negativity subsided, though the area around Rua da Boavista, Rua do Poço dos Negros, Rua Poiais de São Bento, etc., still left a bad taste in my mouth—it’s being overrun with Scandinavian-style coffee shops, natural wine bars, hip designers, etc., in a way that resembles, say, Mitte in the early 2000s; from the many “Please respect the neighbors” signs, it’s clear that hotels and Airbnbs are squeezing out residents.

What’s the solution? (Beyond the obvious, which is simply not to go to a place suffering overtourism—yet here I already was, of course.) I’ve already seen Barcelona changed irrevocably by massification; Menorca, where I live, is beset by problems caused by tourism. It’s my understanding that certain policies instituted by Lisbon only exacerbated matters—such as the digital-nomad provisions, which encouraged foreigners to come live and work in Lisbon, bringing an influx of spending but raising rents and property values in the process. (I looked at a few listings on real-estate sites, out of curiosity, and the property prices are shocking.) So perhaps a first step would be to undo those laws and policies. Another, perhaps, would be restricting or even prohibiting Airbnb (as Barcelona is trying). If I were in charge, I’d ban the tuk-tuks, too. But what then? Perhaps, in the digital age, there’s no stopping it. Perhaps the confluence of Google Maps and user reviews spells doom for any place, since the number of people who become aware of any given attraction (restaurant, bar, vista, etc.) outnumber its capacity by orders of magnitude. So many people are searching for the “real” thing (pastas de nata, or tins of fish) that simulacra spring up everywhere, to satisfy the demand. I don’t know. I don’t have any answers at all, but I do think it’s something we all need to be thinking about much harder, if we want to hold back the locust hordes.

And I will add: The people of Lisbon were absolutely lovely, unfailingly, particularly in the small shops and restaurants. Far lovelier than they had any reason or obligation to be, seeing as how my own family was part of the tidal wave engulfing them.

I failed to make it to Flur, the record shop run by the people behind Holuzam, but we did get a little bit of culture in. The Gulbenkian museum was fantastic; there’s an incredible show on right now focusing on Portuguese-Brazilian artist Fernando Lemos’ relationship with Japan. I wasn’t familiar with his work before, but I fell in love with the calligraphic—almost cuneiform—shapes of his paintings and drawings. Another temporary exhibition, Tide Line, links Portugal’s Carnation Revolution of 1974 with the idea of revolution more broadly, extending it to realms geopolitical, environmental, ecological, and more. In addition to specific works that caught my eye and stuck with me—like Amadeo de Souza-Cardoso’s 1912 painting Mountains—I loved the way the 80 pieces in the show, many of them recent acquisitions, struck up conversations with each other, trading ideas back and forth. It’s a rewardingly dynamic show. My favorite pieces, bar none, were a pair of 3D animated videos by Miguel Soares, from 2004 and 2009, respectively. H20 is a bizarre animation featuring underwater scenes of civilizational detritus (luxury cars, Easter Island heads, exercise equipment, sneakers, Dr. Pepper cans, computer keyboards) surrounded by schools of fish. The music of both pieces was out of this world—strange, spindly abstract synthscapes with a hyperreal edge. The whole thing reminded me of early Oneohtrix Point Never, but predating Lopatin’s work by several years.

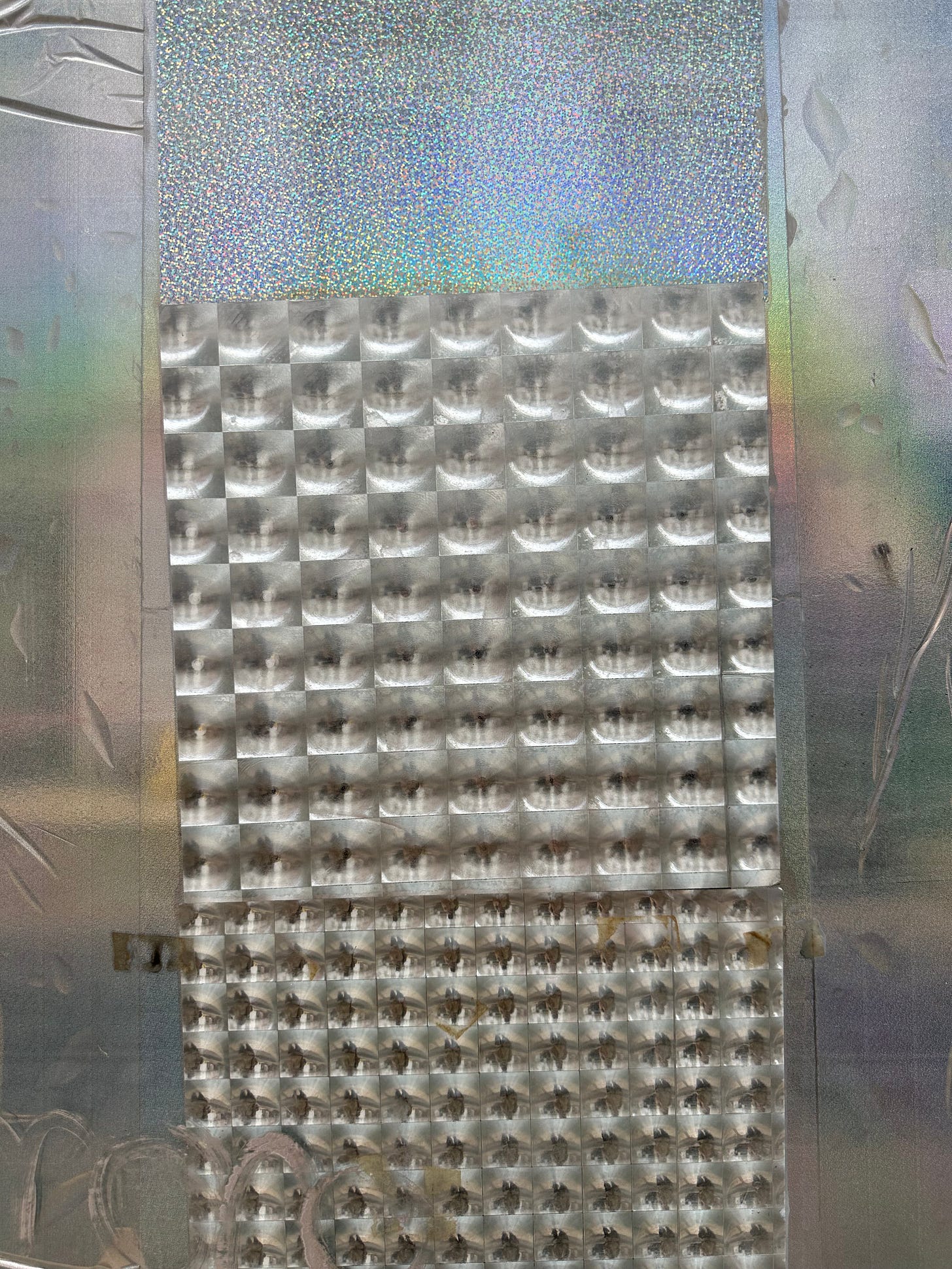

By great luck, I managed to make it to one musical event: a hybrid performance/installation by Alexandre Estrela that ZDB (Galeria Zé dos Bois) put on in the Teatro São Luiz. It’s a difficult piece to explain, but I’ll try. The performance consisted of three consecutive trios performing to a hybrid physical/digital “score” in the form of one of Estrela’s objects, a sort of metal plate that resembles a tape machine. Digitally animated “tape” runs on a loop through the spools of the machine, in three different colors—red, yellow, blue—each of which corresponds to a different player. (Here you can see an example.) The color of the tape changes, seemingly at random, and as it passes through a virtual tape head, the color determines which of the three players is heard. When the tape is black, all three are audible together; individual colors trigger a choppy back-and-forth exchange between the three musicians’ streams. The set I attended featured guitarists Rafael Toral and Norberto Lobo with vocalist Inês Malheiro. The three musicians established a kind of loose parallelism, weaving in and out of each others’ tonal and textural zones; Estrela’s digital sculpture did the rest of the work, imposing a provocative frame of discontinuity on top of them—singling out individual moments to highlight, forcing automated juxtapositions, and occasionally allowing all three to coexist. Like all improv, it was radically democratic, but it was also ordered by the imposition of a system. The music wasn’t reliant on musicians taking cues from one another; each coexisted on his or her plane, letting the machine sort out their signals. With tourism on the brain, I looked for metaphors: Maybe the solution to massification is simply stronger regulations, since individual decisions will always create conflict.

Walking out of the theater in the dark, it took me a moment to realize that someone was calling my name, and I turned my head to see DJ Marfox—who was scheduled to perform in the final trio of the night—standing on the sidewalk. When he and I first met, more than a decade ago, we spoke in a kind of Spanguese (Portuñol?), which we picked up seamlessly. He told me a little about what he’d be doing that night—playing synths and loops, he emphasized, rather than DJing, as he usually does. And he told me about a new generation of local DJs that are coming up, playing a homegrown mix of Afrohouse and diasporic beats; he’d just hosted a group of them at his night at Lux Fragil. It was a good reminder to me that as bleak as things could look from the outside—the obscene rents, the hordes of DJs, the endangered businesses—there’s life under the surface, if you know where to look. The people making real culture will continue to find a way.

There are no recommendations this week; I’d hoped to write up a full batch upon returning home from Lisbon yesterday, but the Barcelona storm and subsequent Vueling cancellations scuppered those plans. And with the election on today, I expect everyone’s eyeballs are going to be glued to the news, in any case. I’ll be back with a proper roundup next week.

Thanks to everyone that shared Lisbon recommendations with me. It’s an incredible city, and I hope to be back soon.

Today’s newsletter is free to read for all, thanks to the generous support of paying subscribers. Those kind souls are duly rewarded with access to exclusive playlists for chilling and clubbing (now at 25 hours and 19 hours long, respectively), the semi-regular Mixes Digest posts, and full access to the archives, including interviews with Belong, Seefeel’s Mark Clifford, Kompakt’s Michael Mayer, and more.

Thanks for reading!

It is weird in cities like Lisbon or Barcelona or Madrid or Seville or San Sebastian, or I guess Paris also, and other places, using Google maps and having to ignore all the highest reviewed things because they're all like tourist-centric versions of the local thing.

Then you find a place or return to an old place you know is really great and it has a lower mark because they probably serve more... 'authentic' food, or don't cater to the more demanding and rude tourists, or whatever, but you know it'll be fine if you go along and are polite and calm.

And I mean ALL of those feelings are weird and that entire process is weird, feeling like "am I the good tourist because I ordered the offal" or whatever, or because I didn't insist on having things my own way, or because I tried to speak the language.

Still rather be that than obliviously rude but I guess the feeling of guilt you mention is what I mean, as I've definitely felt the same, and it is strange trying to travel and not be a problem.

And it's also true that there's always a worse tourist than you in earshot, someone pointing at things or refusing to even try a please or thank you in the local language or whatever, but then there's that same neurosis of feeling as if judging them is exonerating yourself, etc!

Great choices! Hope you had a good time in my city (Almada). Peripheries could act as a centre of counter-power to touristification. Instead, they imitate Lisbon's downtown worst vices. Thanks for the reading