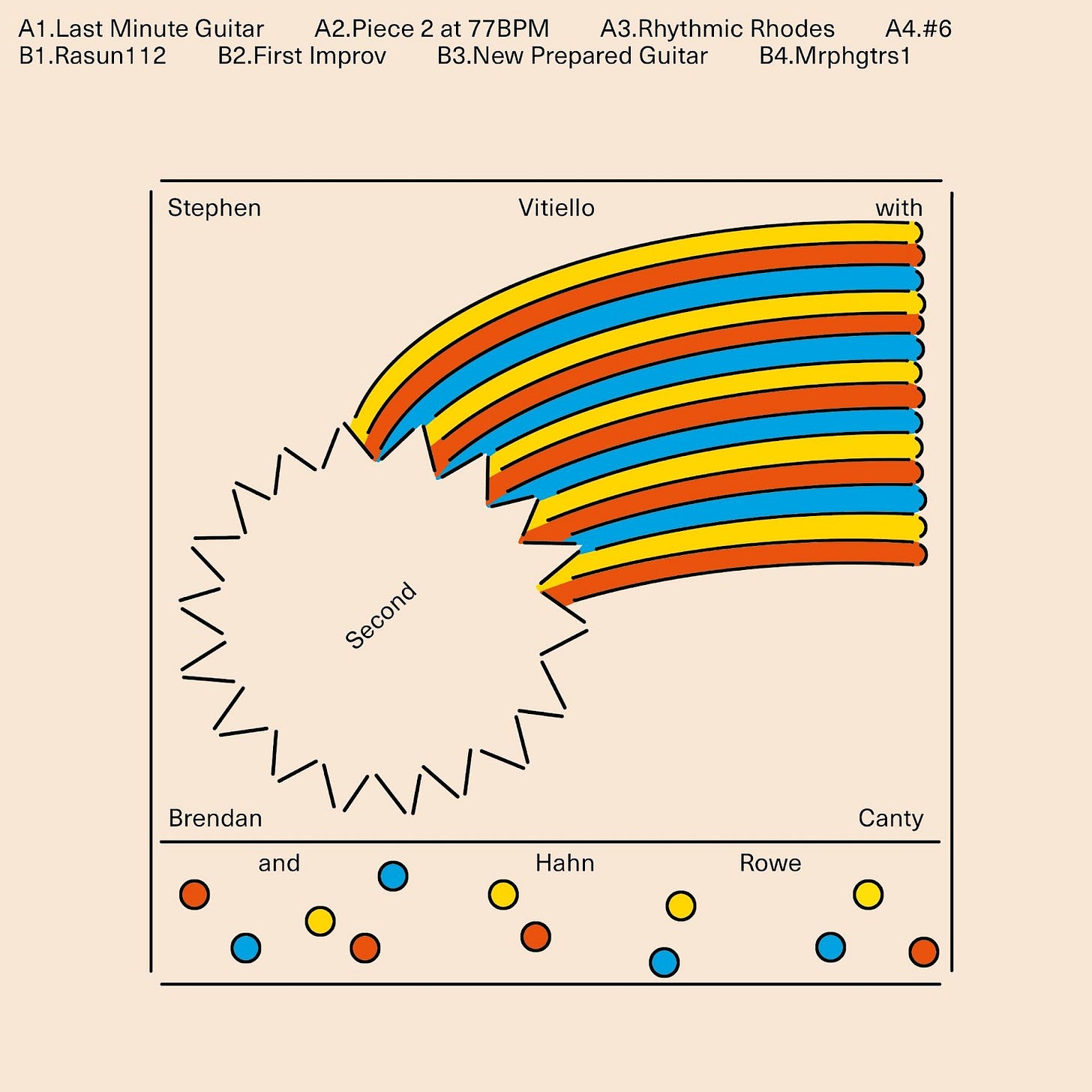

Futurism Restated 108: Stephen Vitiello on his new LP with Brendan Canty and Hahn Rowe

Ambient improv meets post-rock and dub—not to mention the combined legacies of Fugazi and Hugo Largo—on the trio's forthcoming album for Balmat

A funny thing sometimes happens when you run a record label: A demo comes across your desk that causes you to reconsider what you thought your label was all about.

I had always thought that Balmat was an ambient label, more or less. When asked what kind of music we put out, I’d usually say “ambient-adjacent,” just to leave us some wiggle room. We have a pretty broad definition of the genre, of course; nevertheless I always thought the zone was pretty clear.

Then I heard the demo of Second, by Stephen Vitiello and a small group of collaborators I’ll get to in a moment.

It was Andrew Khedoori, of Longform Editions, who passed me the demo and made the introduction; he’d put out Stephen’s group’s previous recording, First, in 2023.

I’d known Stephen’s work since the early 2000s, particularly his collaborations with artists like Taylor Deupree, Steve Roden, Tetsu Inoue, and Lawrence English; given his history in microsound and experimental music, I figured I knew what to expect from a demo from him.

But when I listened to the album, it turned out to be something completely different, something beyond even the post-rock sprawl of First: a mixture of post-rock, dub, krautrock, and free improv—not a million miles away, perhaps, from groups like Joshua Abrams’ Natural Information Society. That comes down in part to his collaborators: Brendan Canty and Hahn Rowe. The presence of either of them, much less both, made me immediately want to put out the record.

Hahn has played with, or produced/engineered, scores of artists over the years—Herbie Hancock, Gil Scott-Heron, the Last Poets, Roy Ayers, John Zorn, Glenn Branca, Swans, Live Skull, Brian Eno, David Byrne, Anohni, R.E.M., Yoko Ono—but most notably, for me, he was a member of Hugo Largo, the New York proto-post-rock quartet I wrote about in FR94. Their 1988 album Drum made an enormous impression on 17-year-old me; it remains a life-long favorite.

Then there’s Brendan, who surely needs no introduction, as the drummer of Fugazi and, before that, Rites of Spring—two of the most influential and beloved bands in my life. (The first piece of music writing I ever did, in fact, was a review of a Fugazi show at Vassar College in 1992 or ’93.) The idea of getting to put out an album with those artists on it was, frankly, mind-boggling. (As an extra bonus, Animal Collective’s Geologist is even on one track.)

Still, I was afraid that maybe the album wasn’t “Balmat enough,” that I was letting my sentimentality get the best of me. Some of it is gauzily atmospheric, but for long stretches, it’s surprisingly muscular, thanks in large part to Brendan’s deep-in-the-pocket drumming.

Fortunately, my partner, Albert, assuaged those fears. When I sent it to him, he simply said, “We have to put this out.”

And so we are. Second—thus named because their first record, on Longform Editions, was called First—is out June 6. You can listen to one track, “Last Minute Guitar,” now.

In putting together the press release, I had an extended chat with Stephen that I’m running here in its entirety. Read on for the full interview, in which we discuss how the trio came together and made the record; why he’s interested in making heavier music now, after decades of lowercase sound; and that time he auditioned for Yo La Tengo.

Today’s newsletter is free to read for all, thanks to the generous support of paying subscribers. Those kind souls get access to exclusive playlists for chilling and clubbing (now available on Deezer as well as Apple Music and Spotify); the semi-regular Mixes Digest posts (the next one coming soon!); and full access to the archives, including interviews with Penelope Trappes, Longform Editions head Andrew Khedoori, Bristol bass trickster Bruce, drone titans Belong, Seefeel’s Mark Clifford, and more.

How did the collaboration between you guys come together? I know that the three of you did a recording for Longform Editions in 2023, and you’ve done stuff with Hahn going back, I think, 25 years or so. What was the genesis of all of this?

I did an EP with Brendan four or five years ago. I first met Brendan through Rebecca Gates—do you know Rebecca?

Oh yeah. Big Spinanes fan.

She was guest-teaching at my school, but I’ve also been in at least two things that she’s curated. Many of my relationships, there are sort of multiple tiers. Rebecca brought Brendan in as a visiting artist. And for me, Fugazi and Hugo Largo are two of my favorite live bands of all time. As Brendan was walking out after the talk, I said something a little bit fannish, but also made some connections—he’d seen a show I did with Jem Cohen, the filmmaker, many years ago. And he said, “Well, if you ever need a drummer…” It was like, really, or are you just being polite? And I followed up, and we did a session in DC. I remember on the way home, I was so nervous, and he texted me and said, “I love your stuff,” in capital letters, and I got very happy. So we did this EP for a small British label that went defunct, but it came out digitally.

I wanted to keep working with him. Part of what I love about it is that I create these textural pieces that have implied rhythms, implied melodies, but not everybody would know where to even grasp them. Brendan would find ways to get a center, as my rhythms were going off in directions. Once we established a relationship, I thought, the next thing could be to bring in melody. And that’s where I got the idea of bringing in Hahn, who’s such an incredible multi-instrumentalist—gorgeous ear. Actually, it’s funny thinking about Hahn. When Robin [Rimbaud, aka Scanner] had the Meld series through Beggar’s Banquet, like 2001 or 2002, I had a sort of Tricky-inspired CD that Hahn did turntables on, called Scratchy Marimba.

We’re coming from three different schools, between sound art, punk rock, and, you know, art rock. So I was excited for the melding of these different styles. Then also just the brilliance of their playing. Each time the other would hear some overdubbed tracks, they’re like, “Wow, that guy’s good.”

Is there a particular conceptual framework for the record?

You know, sometimes my projects are really conceptually driven. I think this was more musically geared. I don’t know if post-ambient is a proper term, but I wanted just to open up the references and bring in an incredible drummer, bring in some melodies, and I’m sort of the center. But they’re also vastly creative in making anything I might suggest better.

And then Geologist is on one track.

That was a nice coincidence. We were recording in a studio that Brendan likes in the DC area, Tonal Park, and he said, “Brian from Animal Collective is in the building, if we have a track that’s in”—I think it was C—“and you want hurdy gurdy, he’ll come in.” He didn’t know me or who I was, but he knew Brendan. And he listened to one track, which was “Mrphgtrs1,” which at that point was just me, and pretty much nodded his head, sat down, and played hurdy gurdy for the straight 10 minutes of the raw track, said, “That was cool,” and left. I love these chance encounters. Again, somebody I admire, a group I admire—that was an unexpected gift.

Don Godwin’s on there too.

Right, he’s the engineer. It was getting toward the end of the day, and there was one piece where all the rhythms are from me, so Brendan went in to record some overdubs. And Don said, “Can I go in there and add some stuff too?” He had this dustpan that he calls the “resonant dustpan.” He jammed. But he’s also a brilliant engineer.

Don was also in that group Reanimator, from Portland—they had a record on Strategy’s Community Library label. As a Portlander, I was always interested in what they were doing.

Yeah, he’s great. The studio’s in Takoma Park, and I didn’t realize, until Brendan was driving me to the train, he’s like, “You know, this is Takoma Park, like John Fahey’s Takoma Park label.”

No way.

Anyway, working with Brendan, the conditions are sort of like, OK, here’s my schedule, here’s the studio I like. And then he and I come in, and he’s a pro and a powerhouse. Brendan adds a lot. He’ll add piano, he’ll add guitar. On the EP, I remember he added this African drum we barely used, but he just brought in the kitchen sink to see where we could find our collaborative language.

Basically the gist of it all is that Brendan and I did an EP; then we did this extended piece with Hahn for Longform Editions. And the success of that, some nice feedback—including your newsletter—made me feel like it really deserves a full album. It pretty much started in my room, then I went to Brendan, and we recorded together in the studio, so there was some give and take. Then I went to New York with Hahn.

So it wasn’t a mail-in kind of project.

Yeah, I’m the constant. I wish we could have played in the same room, all together. But I swear, this one more than anything feels like it could almost be a cohesive group.

I wouldn’t have guessed that it was recorded piecemeal—it doesn’t sound like that. Could you go into some more detail into your playing and how the tracks begin? You talked about starting with these little pieces of implied rhythms. What’s the initial kernel?

I use sampling a lot, but I always sample myself. There are two tracks that started with acoustic guitar, two of the funkier pieces. Or I’ll record some electric guitar. One track is an old 1970s Rhodes keyboard. And then I’ll input that either into the modular as a sample player, and trigger lots of LFOs and random generators that are picking and choosing from the file, or I’ll do it similarly in Ableton using Granulator or Simpler. Then everything is a kind of performance, so I’ll get a setup going and start recording, and then often it’s like 10 or 20 minutes of jamming with my own source material, trying to keep changes happening. Rarely intending for it to build in a particular direction; just listening and using the tools, often multiple delays. Like watching those videos of Daniel Lanois remixing, he always uses that Prime Time delay that has a looper function—that’s not unlike the way I think, which is just to have a couple key pieces of gear that also become an instrument, and allow me to sustain an idea over time.

And so then when you take one of those to Brendan, have you edited it down from that 10-20 minute session, or are you really bringing him the raw material and performing that live alongside him?

In most cases, unless I’m playing live piano in the studio or something, basically I’m coming in and thinking, OK, we’ve got a day of studio time: Prioritize Brendan. I’ll play him pieces, get his feedback. It’s generally coming with a relatively finished piece. And then once he adds his part, and once Hahn adds his part, then we might start saying, you know, you can’t always do 14-minute pieces. For some reason, length—maybe that’s a sound-art thing. Same with Steve Roden and other close friends, sometimes I just wanna keep doing 40-minute pieces, but in this context, trying to bring it closer to relative song length.

And then once they’ve recorded their parts, are you doing significant editing and post-processing to those?

Yeah, yeah. Both me and Hahn. I’ll do the initial structure of editing and then Hahn will add overdubs as he goes. Sometimes that’ll mean just taking things away. We did some cheats with Brendan. Everything we’d done up until this album, I just took his drums as he would play them. But here, in some cases, he’d say, “All right, I’m giving you three ideas, you figure it out.” And because the pieces are so repetitive, we could just go A,B,C, but Hahn, particularly with rhythm, went in and did a little more editing—like, Brendan just played it fantastic here, let’s let that play out for two minutes, or whatever. And punctuate it with other sounds.

The drumming—at times it’s unbelievable to me how muscular it is. Or not unbelievable, I guess, because it’s Brendan. But I love how you think the record is going to be one kind of thing, with the opening track, and then with the second track, it starts out kind of mellow and then builds into this behemoth.

That one gave me smiles all over. That’s probably the most structured song. I was so proud of that track.

I get the sense that collaboration has always been a really significant part of your practice.

I love it. I grew up in New York, and now I’ve been in Virginia for 20 years, so it’s a way I stay creative and stay social, with these networks of friends elsewhere. The same for me as a sound artist where I make site-specific installations. I often do best when I’m responding to something, responding to a space.

My creative education was doing soundtracks for video artists, which is another form of response. Now, with these kinds of projects, you always try to figure out—is somebody in charge? Are we going in as equals? But what I love is where it’s a dialogue. So whether it’s the rare cases where I played with Ryuichi Sakamoto, or playing with Steve Roden or Taylor Deupree, where we’re really just having a duet—that’s one kind—and then there’s these other things, like this album, where maybe I’m the driving force, but I’ve got people who, from my point of view, have complete creative freedom.

This one feels sort of like a classic jazz bandleader album where you’re the fulcrum, but everybody holds equal weight in terms of realizing it.

I think that’s the thing. Even with the credits, where I had to reach out to Brendan and Hahn and say: How do the names go? And that was how they saw it too. I had an experience once that was a long track of mine, and then another artist remixed it. So I had my name first, and this other artist was like, no, it had to be alphabetical. We had this weirdly big fight about it. So I’ve tried to be careful, because it’s better to keep people’s friendship and respect. But I’m glad, and I think it makes sense, that Brendan and Hahn saw me as sort of bringing it and producing it, but they also felt excited to have their names on the marquee.

Right, they’re not just session players.

Not at all.

I tend—maybe wrongly—to associate your music with much quieter styles. Do you feel like this project is kind of a departure for you?

I think it’s a return. You know, the first bands I played in, in the late ’70s, were punk rock. And then sort of Factory-related bands in the ’80s. I mean, people actually connected to Factory Records were in these unpublished bands. But then it got much quieter. That record I made for Robin Rimbaud—Sulfur Records was the label, I think it was called the Meld series—that was rhythm oriented, with really powerful live drums. In some ways it’s just a return to those interests, I think. And I’m getting sort of drained—ambient has become so prevalent.

You know, seeing effects boxes marketed basically as “instant ambient.” I remember the licensing people who worked with Sub Rosa, when I made a CD there, I talked to them about doing soundtracks. And they said, “Well, drones are easy.” And in some ways I was offended, because I thought, nothing is easy to do well, and I don’t even hear what I do as drones. But somehow all of those things have been pushing me stylistically away from quiet, or at least only being quiet.

In an email, you told me how important Hugo Largo were to you in your youth. In fact, you even auditioned for them.

I did, yeah, a couple of times. When Tim Summer left, I auditioned. They were sharing a studio with Sonic Youth, in a basement, and they said, you know, we might have you join the band—you could play Farfisa—but you’d have to stop going to college. And I was like, no. Then, when Adam left, I auditioned for a couple months, and then that didn’t happen. But I really loved them. I would go to every show I could. The artfulness—the two basses, violin or viola, with a kind of performance-art vocal—really influenced me in what feels like post-rock before I knew it was post-rock. And in wanting to play in bands that were like, Throwing Muses on one side, and Hugo Largo on the other. Being in New York, I always had friends I played music with—I had a lot of almosts.

You said you even auditioned for Yo La Tengo?

Yeah, that must have been early 1986, I’m thinking. I was playing bass, and a student at SUNY Purchase, and went out to Hoboken and auditioned. I think it was Georgia who said that I played the pretty songs nice, but Ira said I couldn’t really rock. They’re like, “OK, let’s do some Love covers.” And I didn’t really know Love. What I knew how to do was play like Hugo Largo, even before I met Hugo Largo. Everything on the 12th, 14th fret of the bass, plus Peter Hook influences, the Cure influences. But you know, Yo La Tengo is probably one of my top five bands of all time. So I do feel fortunate that I had almost moments with people that I still think about 30 years later.

What was your listening relationship like with Fugazi?

I was primarily a fan of Fugazi live. I’d done some sound work for Jem Cohen, the filmmaker.

He did the film on them.

Instrument, right. I remember he brought me and another friend to Trenton, New Jersey, the first time I saw Fugazi live. I was just knocked off my feet. From my punk-rock days, I was more into Bad Brains and some other bands, but I don’t think I really understood the power of Fugazi until I heard and saw them live. Rites of Spring, Minor Threat, I was less aware of, but all of the things that people talk about—their ethics, their goodwill, I was so impressed by.

I think I saw Fugazi four or five times. I know I saw them at Vassar; I reviewed the show, which is actually the first piece of music criticism I ever wrote. I tried to see them at a place called Blue Gallery, in Portland. I think it was the summer of ’89. They were on tour with Beat Happening, and Jerry A. from Poison Idea was at the door, reeking of whiskey, like, “Fugazi’s not here, man, their van broke down.” I was like, are you kidding? I didn’t know if he was fucking with me, this little 17-year-old semi-straight-edge kid. But no, their van had broken down in Olympia, I think, so I didn’t get to see them, and I was heartbroken. Then maybe in Providence, and once in Portland, Maine, and then years later in Dolores Park, in San Francisco. But yeah, they were incredible live.

It was so much the bass and the drums. But then the guitar interplay, too. I mean, my favorite album of all time is Marquee Moon. The guitars of Sonic Youth, the basses of Hugo Largo, the bass and drums of Fugazi—I’m so drawn to these kinds of dialogues, which maybe fits with my interest in collaboration. Or learning to play Bach’s two-part interventions on the guitar, both parts. I love the interweaving of lines. That’s what I hope comes through on this album. Even where it’s dense, we’re all playing off each other very consciously.

Would you like to take this a step further and do and record all three of you together in a more live-in-the-studio context?

Yeah, that would be ideal. We tried to make it happen. I tried to get Hahn out to the studio with Brendan when we did that session, but he couldn’t make it. Somewhere along the line, that would be a treat.

This is stunning! Pre ordered!

All signs point to another heater from the label that refuses to miss.